Thomas Alma Moulton claimed his homestead on Mormon Row in 1907 when he was 24 years old. His cousin George Jr. made the application for the land, but when the filing was close to being granted, George had changed his mind and offered the land to Alma.

Thomas Alma Moulton claimed his homestead on Mormon Row in 1907 when he was 24 years old. His cousin George Jr. made the application for the land, but when the filing was close to being granted, George had changed his mind and offered the land to Alma.

Along with his younger brother, and a neighbor Thomas Perry, Alma saddled his horse, and left the family holdings in Idaho for Jackson Hole, Wyoming. There on September 9, 1907 Alma filed on the homestead his cousin had chosen earlier. John took an adjacent claim. Both were on the straight lane known as Mormon Row.

Perry made his own claim for free land across the lane to the south and east. The three them returned to Idaho to herd sheep. Alma also served an LDS church mission in the Boston area. It wasn’t until 1908 that they returned to Jackson to begin the process of proving up on their claims. A year later another Moulton brother, Joseph Wallace Moulton, would join them.

The next couple of winters found Alma in Idaho herding sheep, but during the summer he was in Jackson Hole making improvements to the homestead and fulfilling the residency requirements of the Homestead Act. Alma built a 14’ by 18’ cabin with a sod roof.

Tears rained down his new wife, Lucile’s cheeks as she walked into the one-room homestead cabin carrying a new baby named Clark in her arms.

A shelter for the animals was as important to the family as a house and water. Horses and cattle provided transportation and food, and without them survival at Grovont would have been nearly impossible.

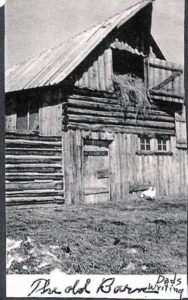

Alma’s barn is of the style common to the era and is not particularly unique in any way. It would be decades before he completed the barn, and part of a century before it would become a symbol of America and the struggle and perseverance of a homesteader. No thought was given to how to match the angle of the mountains behind it, only as to best house there animals against the harsh weather that is Jackson Hole.

Alma started construction of the barn in 1913. It would provide a warm place for Don and Saylor, the draft horses. They were nearly as important to the family’s survival as Alma himself. They deserved a shelter. Lodgepole Pines were cut from Timber Island and skidded home using the team of horses. The first section of the barn was laid out in a 18’ wide by 24 feet long box, 12 rows of logs high. The roof was flat, and made with slabs Alma got from the sawmill in the nearby town of Kelly. The barn was in this configuration for nearly 20 years.

In 1928, Alma and his son Clark, who was now 16 added five more rows of logs to make a hayloft, and a half pitch roof on the original box-like structure. In 1934, the added a lean-to for the horses used on the mail run from Jackson to Moran Junction. By 1939 the family’s livestock had outgrown the available space. So Clark and his 18 year old brother, Harley built a hog barn on the north side, topping it with a tin roof. The family’s dairy operation took place in the original center section, and the horses used the south side lean-to.

The Moulton’s watched in amazement when Henry Fonda arrived to their barn one day during filming the movie, Spencer’s Mountain. In the first stall on the south side of the barn, Fonda struggled to Milk the cow, Blossom, a chore any self-respecting 8 year old could do on the ranch.

Alma and Lucile added another 6 children over the next dozen years. A frame house soon replaced the crude cabin providing a better place for Lucile to raise her children.

From the earliest days when the Moulton’s came to America as part of the Mormon Handcart contingent, they were deeply religious. Lucile and Alma both served the LDS Church for many years. She was Relief Society president for 26 years, and he was The Presiding Elder for 29 years. They firmly believed in the teachings of the church and were self-reliant, always putting family first. Although they knew the church would help them if they were in need, the Moultons adhered to the philosophy of “chasing your own rabbits” rather than relying on others to provide for them.

As part of his responsibility to the church, Alma went to the small white building standing midway on the lane early every Sunday to start the fire. Sitting by the pot-bellied stove waiting for his little congregation to arrive, Alma bowed his head and studied lessons from the Bible and Book of Mormon.

The first years the Moulton’s lived at Grovont, life was particularly hard. They had no irrigation system, so they dry-farmed the land until the late 1920’s, trusting that adequate natural moisture would come to make a crop. But the rain didn’t always fall, and after one particularly dry summer, Alma had little feed for the forty head of cattle he had struggled nearly 20 years to acquire. He bought what hay he could afford at fifty dollars a ton, but money was scarce, and the amount of hay obtained was not adequate for a long winter in Jackson Hole. Before spring grass turned green, Alma was out cutting willows and Quaker trees to feed his cattle. A little straw and oats supplemented that fodder.

After that experience, Alma filed for an irrigation water right on September 25, 1929, out of Mud Spring, a tributary of Ditch Creek at the Gros Ventre river. It took seven years to get a permit approval and to build the ditches that would carry water to the Moulton Land and other homesteads in the area.

Winter snow banks covered the fences as the temperature plunged to forty and fifty degrees below zero. Every day men hauled water, fed their livestock, and provided for their families. It was an unyielding cycle in a harsh climate. During the weeks between Thanksgiving and Christmas, the smell of baked goods drifted from homes along the row as the women did their best to give joy to their children. They bustled about making Christmas presents: particular gifts such as knitted socks, mittens and scarves.

Alma, Wallace, and John headed up the Gros Ventre Canyon to chop wood for the winter. On the final trip they would always cut a Christmas tree for the children to decorate with homemade ornaments, strings of popcorn, and colored paper.

The homesteader’s would mark Christmas with a special worship service at the little white church down the lane and a Christmas pageant at the school just next door. Produced by the children and their teacher, the pageant was a gala affair highlighted by music and laughter, home-baked goodies the women provided, and a visit from Santa Claus.

As winter lay over the land, Alma hauled water for the house needs and the livestock, struggling through deep snow to feed his animals, Lucile spent her days and nights sewing clothing for her family and others in the area. Quilting was a favorite pastime, with a section of the living room always brightened by the pieced top of the current project. Lucile sewed the top and then tacked it to a frame sitting atop the backs of four chairs. As the snow fluttered or came in fierce, blinding blizzards, she sat by the fire, deftly pulling her needle up and down through the quilt layers stitching a design.

Lucile received wool from her father every summer to wash and store in sacks. During winter days and nights the children sat at her feet and picked the wool to clean it before she carded it for various creations.

Lucile’s life on the homestead was not unlike that of any other women of her generation. She had children and took care of them by cooking, sewing, cleaning, and nurturing as the need arose. She acted as doctor and nurse, and as a teacher if called upon. She raised a large garden that provided food and snacks, like carrots, fresh peas or turnips. She made soap, cured meat, canned fruit she picked wild and vegetables she raised in her garden, milked the cow if no one else was around to do so, and raised a few chickens for the eggs they laid or to stew with dumplings or noodles.

Like other women on the Row she sold butter, eggs, cream, and milk to get a little cash money for the necessities that the family couldn’t make or grow on its own. Primarily, however, the Moulton’s were self-sufficient and did not rely upon outside products for survival. Lucile seldom went to town, making the trip only once or twice a year for supplies, riding in a wagon or horse-drawn sleigh with blankets over her knees and warmed rocks at her feet to ward off the cold,

When her domestic duties were done, and sometimes even when they weren’t, she headed to the field with Alma to grub sagebrush from the land or help with the planting. With no machinery to do it, grain was sown by hand. Alma put seed in tubs, and buckets and loaded them onto the lumber wagon. Lucile drove the team while Alma broadcast the seed. The children went along for the ride. Eventually Alma and his brothers saved enough money for a drill and other machinery.

Lucile’s one real source of pleasure was her buckskin mare Sally, whom she loved to race across the fields. But when Alma needed another draft horse for the work on the homestead, so he sold Sally. That act broke Lucile’s heart, and she never fully forgave him.

Courting was down the lane. Young Clark Moulton lived on the north end of the Row. Veda May lived on the south end. He hitched a team to the sleigh and took a box of chocolates to go visit a girl. “Grandpa May had a dog that hated me with a passion. I had to carry a lot of jerky to get down there and needed more to get back,” Clark said. His persistence paid off and the two married. They had three children whom they reared on Mormon Row.

Clark’s eldest sister Melba also married a May, as Veda’s brother Lester would come courting from his end of the lane. Once married, Lester and Melba lived on Mormon Row for a time with their five children.

Alma and Lucile’s youngest son, Harley, left for a time to serve in the U.S. Army Air Corps during World War II. He was with the first contingent of U.S. troops went into Japan after the armistice. Arriving home on Christmas eve of 1945. Lucile was overjoyed with his return. Harley would marry Flossie Woodward whose Grandparents had also homesteaded in the vicinity.